This article contains sexually explicit material.

The Erotic Memoirs of a Male Chauvinist Pig, Champagne Orgy, Massage Parlor Murders. Ryan Emerson knows the basic reason why someone would want to visit Exploitation.tv:

“Blood and sex, that’s what people want to watch.”

Emerson is the co-founder of Exploitation.tv, a streaming site devoted to exploitation films, and Vinegar Syndrome, a Connecticut company that restores cult and exploitation films from what many would argue is the genre’s golden age: the ’60s-’80s.

Vinegar Syndrome originated in Chicago in 2012, after Emerson and co-founder Joe Rubin were brought together while working on the digital restoration of the 1975 horror film Poor Pretty Eddie.

“We just got to talking after that and decided to start a film archive in Bridgeport, Connecticut, with a couple of other partners,” Emerson said. “A couple months later, we founded Vinegar Syndrome.”

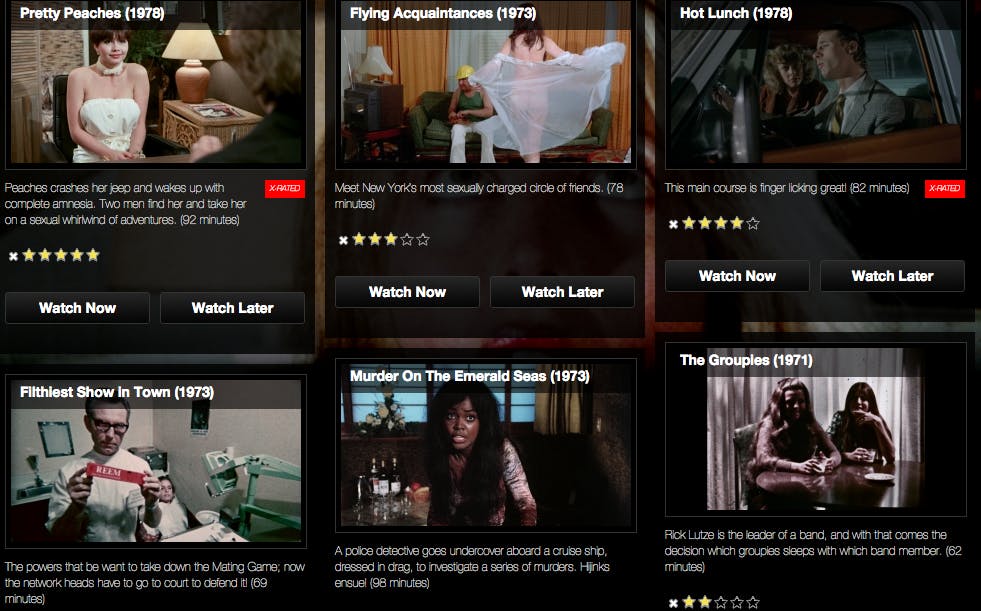

Exploitation.tv, which launched Sept. 1 on the Web and Roku, (it’ll be available for iOS and Android later this year), is Emerson and Rubin’s attempt at putting these films—Emerson says they’ll have more than 300 available—in a more modern cultural context.

“It’s a genre that’s long been underappreciated,” he said. “The exploitation film era from the ’60s through the ’80s—some of the most lost films come from that period.

“You’re not going to find these on Netflix, you’re not going to found these on Hulu,” Emerson added. “Exploitation.tv is going to be the only place to see the vast majority of these films.”

Emerson’s favorite film in the archive, Nelson Lyon’s The Telephone Book, was one of the first titles Vinegar Syndrome updated. “I think that film really encompasses what we’re all about,” he said. “And until we released that film, it wasn’t really available anywhere. And it’s experiencing kind of a cult-like resurgence in the last couple years. It’s really neat to see that happen.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lCU2fZYM6o

Exploitation.tv is searchable by genre—action, arthouse, comedy, drama, horror, thriller, and shorts—and you can find more well-known classics like Jess Franco’s Vampyros Lesbos, House of Seven Corpses, and I Dismember Mama alongside obscure titles like Sex World, Did Baby Shoot Her Sugar Daddy, and Hot and Saucy Pizza Girls. Many of these films have been kept alive via film fan sites and IRL screenings like the Alamo Drafthouse’s devotional Terror Tuesday and Weird Wednesday.

Austin Film Society programmer Lars Nilsen, a former Weird Wednesday programmer, says these films still offer some important cultural context.

“It’s always fascinating, and strangely comforting, to see members of our parents’ and grandparents’ generations doing and saying crude things—to get a sense that there was a rudeness and untidiness to life in those good old days,” he said. “Every narrative has a documentary aspect. We’re not only watching a film about, say, a nudist colony, or a gangster war. We’re watching the performers enacting what those transgressive concepts meant to them.”

While there are certainly current films that could fall in the exploitation category (Eli Roth’s long-delayed The Green Inferno, Harmony Korine’s surreal Spring Breakers), and directors like Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez have paid homage to the genre several times over, this type of filmmaking thrived in a much different political, sexual, and social landscape. Exploitation films kept their finger on the pulse of expanding minds, changing mores, and social anxiety while on a low budget. Films like 1936’s Reefer Madness, the poster for which is now a staple of college dorm room walls, blotted out a place for critiquing heightened drug paranoia on the edge of World War II. The ’60s offered Russ Meyer’s take on a new type of feminism—and satire.

“To me, an exploitation film is exploiting a current trend,” Emerson said. “Whether it be a trend in cannibalism, a trend in, you know, in the ’60s with wife-swapping, that kind of thing. It’s exploiting a certain cultural trend of the period; that’s the true definition of an exploitation film. And it encompasses a lot of genres: horror films, action films. All sorts of films could be considered under the exploitation umbrella.”

A large part of Exploitation.tv is X-rated films from the ’70s, a time when the production of pornography was largely unregulated. Several titles focus on rape or kidnapping storylines, and there’s also more than one film where a man “hypnotizes” a woman into sexual acts. With the many conversations currently taking place online, these films might not translate past the kitsch or arthouse tag.

Still, there are several titles in which women (and men) “awaken” to their sexual needs and desires and explore taboo fantasies. In the book Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!: A History of Exploitation Films 1919-1959, author Eric Schaefer posits that “[b]y shaking the entrenched industry’s definition of acceptable form and subject matter, exploitation paved the way for the greater freedoms the screen began to enjoy in the years following World War II.”

Moreover, by simply invoking certain issues, exploitation films offered a degree of freedom for men and women who had little access to information on sex and other topics at a time when such knowledge was restricted by law as well as social convention.

Unsurprisingly, Emerson says the XXX films are the most in-demand titles. We’re at a cultural point where there’s growing interest in vintage smut and schlock, and exploitation films can offer a respite from Hollywood’s desperate reboot culture.

“We’ve been engaged in a culture-wide irony O.D. for over 30 years now,” Nilsen said, “and these dispatches from the pre-irony age (sometimes the proto-irony age) can make us feel alive again and free us from the shackles of these ironic quotation marks, which we all bear like cumbersome and punitive medieval stocks.”

Emerson says that with Exploitation.tv, they’re attempting to add some artistic and historical value to the conversation, not just dangle clickbait.

“When it comes down to it, we’re preservationists at heart,” Emerson added. “We’re preserving film from a certain time period—the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s—and to me that’s the most important thing. To make sure these films aren’t lost. That they don’t disappear forever.”

Image via Exploitation.tv | Remix by Max Fleishman