The moment Beyoncé referenced the site, OnlyFans had arrived in the public lexicon. In her feature on Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage Remix,” Beyoncé namedrops the site early on: “Hips TikTok when I dance (Dance) / On that Demon Time, she might start a OnlyFans (OnlyFans).”

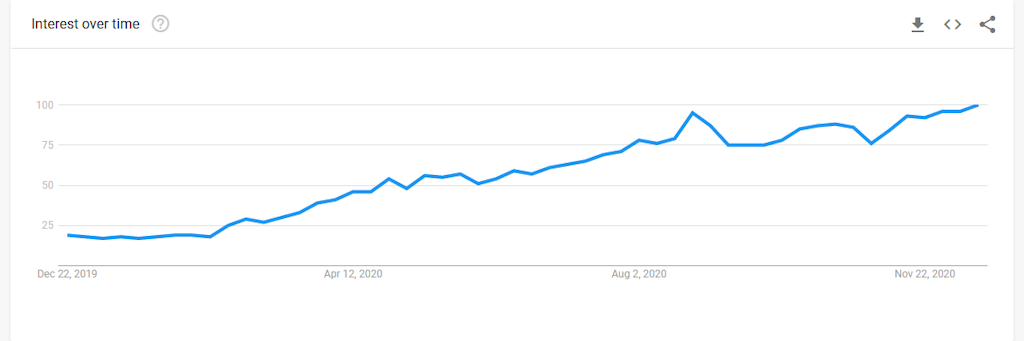

“Savage Remix” came out in late April and kicked up popular interest in OnlyFans across mainstream media and among people searching for supplemental income (or just income, period) during the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic crisis. Now, nine months after Americans began social distancing, OnlyFans is nearly a household name.

On the one hand, the site pushed sex work into news headlines and gave struggling Americans a place to pay the bills. But while OnlyFans’ widespread recognition increases visibility for sex workers’ rights, the site’s popularity impacts sex workers in complicated ways: some good, some bad.

How the pandemic shaped the sex industry

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected sex workers’ income. For offline workers, the negative effects are obvious: clubs shut down, clients became less accessible due to health risks, and regulars pulled out as they lost their income sources or tightened their belts. This immediately forced offline sex workers to figure out a transition to online work.

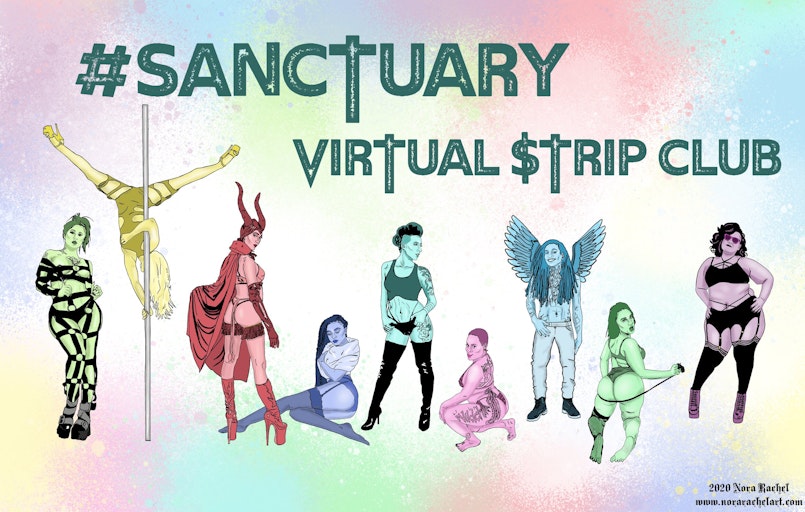

Andre Shakti is the host and proprietor of Sanctuary, a queer and BIPOC-centered virtual strip club. After the pandemic began, Shakti lost 85% of her income within the first week of March alone. When her offline strip club shut down, this was a huge blow to her financial stability. Shakti would dance two to three days per week, and the club gave her the opportunity to network with clients for future work opportunities, including professional dominatrix sessions or polyamory and intimacy coaching clients.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus shut down other income opportunities for Shakti, including conferences and workshops on sexuality and kink. As a result, the only income sources Shakti had left were filming adult clips online and the few coaching clients she could retain.

“I literally lost my entire industry overnight. Every single facet of the work that I’ve been doing for the past 12 and a half years within the sex industry involves closely engaging with other people physically, whether, again, that’s in an explicit way or not,” Shakti told the Daily Dot. “My entire industry just vanished and I was left scrambling.”

COVID-19 has equally affected online workers. Virtual domina Sammy Rei Schwarz, an online sex worker specializing in femdom and giantess play, told the Daily Dot that her income has been unstable since the pandemic began. On the one hand, she’s gained new clients thanks to work-from-home. A “minority” of her clients have more spending available, too. But on the other hand, some of her regulars can no longer spend money on her services, affecting her overall income.

“Even for those who already worked online, switching to solo-only content can be a big change for both your workflow and audience, while those who have never worked online before have faced an even more difficult hurdle,” Schwarz told the Daily Dot. “But it has been encouraging to witness the creativity and resourcefulness with which sex workers in my community have survived and supported each other.”

Meanwhile, it’s impossible to discuss the pandemic without mentioning how Black Lives Matter shaped Black sex workers’ experiences over the past year. GiGi Holliday is a Black indigenous stripper who co-hosts the late-night virtual event Sanctuary Noire featuring exclusively BIPOC strippers. She stressed that the pandemic “hurt us,” but the year’s Black Lives Matter movement “uplifted” Black sex workers “a little bit more.”

On the one hand, this led to more awareness about Black sex workers’ experiences in the sex trade. But after expressing white guilt, many white sex workers failed to maintain their dedication to helping their Black colleagues. And while Black sex workers’ experiences were highlighted and supported during the summer, “when we are uplifted a little bit more, there are definitely people coming for our necks,” Holliday said.

“Black women are always trendsetters. While we didn’t have that one-on-one connection, that in-person connection, we had already decided to do our things online. And a lot of us already had our OnlyFans,” she said. “But now that everyone thinks that the world is ‘back to normal’ we’re still struggling a little bit, we’re back to square one, a little bit. And it’s just keeping that momentum.”

With coronavirus-related restrictions in place, each sex worker devised their own plan to stay afloat. For some, that includes OnlyFans. For others, not so much.

Why did OnlyFans blow up?

According to Google Trends, OnlyFans jumped up in search interest during late February and early March, around the same time that COVID-19 began spreading in the U.S. Throughout the spring, search interest only grew until it briefly spiked from April 26 to May 2, right when “Savage Remix” came out. Interest again peaked in August and late November.

It seems unlikely OnlyFans’ popularity will drop anytime soon. But why did OnlyFans arrive, and how did it get so popular? That history goes beyond the pandemic.

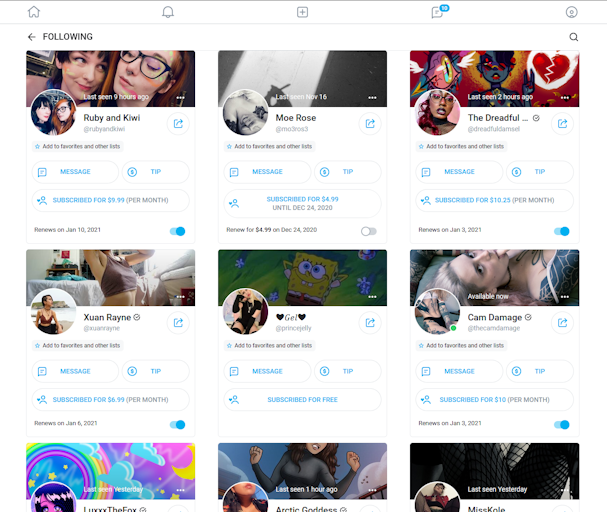

OnlyFans is a U.K.-based social media service founded in September 2016 by Fenix International Limited. The site operates off a model called a “fansite,” where fans pay a monthly access fee for performers’ exclusive material, such as clips, photosets, and audio recordings. There are many other sites that offer the fansite model: AVN Stars, JustFor.Fans, and ManyVids’ MV Crush system, just to name a few. But OnlyFans remains the most popular service.

When the pandemic began, OnlyFans was available to Americans who needed a way to pay the bills, either due to coronavirus-related emergencies or layoffs. But some of the most popular and visible OnlyFans performers are white, thin, and straight, which erases the various identities that actually use the site. Holliday told the Daily Dot that Black sex workers originally found and popularized OnlyFans, but the site grew in popularity when “pick me” women realized they needed a way to make an income during the pandemic.

“It blew up because of that. And not only that. Right about April and May, that was when the whole world realized, oh shit, we’re stuck in the house,” Holliday said. “But I really do think once people realized that it was lucrative, that sex work is real work,” that’s when non-sex workers realized they could use the platform too, she said.

Meanwhile, with social events long gone and quarantine loneliness emerging, adult content became more and more popular. This resulted in clientele ready to spend money on new and recognized sex workers alike selling all sorts of porn.

OnlyFans’ availability also gave offline sex workers an opportunity to pivot their approach as sex workers and reflect on their current work structure. Bella Blue is a stripper for Sanctuary who has an OnlyFans. Before the pandemic began, Blue was working as a burlesque performer and producer in New Orleans, although she had been doing sex work as both a dominatrix and as a stripper since she was 26, she told the Daily Dot. Before COVID-19 arrived, she was already reconsidering her relationship with burlesque and exploring a return to domme work. Online sex work became an option, and she created her OnlyFans in December 2019.

But as the pandemic continued and venues remained closed, Blue decided to double down on online work. She began focusing on her OnlyFans, which she describes as “very wholesome” and a personal reflection of herself. She says for her, sex workers are mediums to “people feeling connected” and experiencing healing, affirmation, and acceptance.

“A lot of my ideas were like, how can I shift to just streams of online income so that I have daytime to rest and to be with my kids and to be with my house and to be with my partner and all of that stuff,” Blue told the Daily Dot. “So then I started to put a lot more effort into the OnlyFans platform and saw a really great response to it.”

OnlyFans facilitates connection with clients, which makes it a great platform between sex workers and their fans. But OnlyFans money isn’t easy money. It’s still a hustle. And OnlyFans is not inherently a good fit for every sex worker. Shakti herself avoided using the site partially because she doesn’t have the time to spare to run one, which involves editing videos, watching analytics, and marketing. She also spoke to another issue: the oversaturation of sex workers on OnlyFans during the pandemic. When the economic downturn hit, OnlyFans was there for many people, causing higher competition.

“There were like hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of thousands of new profiles going up right around the March/April mark where a lot of people were losing their income as a result of COVID and turning to OnlyFans,” Shakti said. “Some of them sex workers, a lot of them people who had never even done sex work before in their lives. Either way, it really saturated the market and it was harder to stand out once March and April rolled around.”

An increase in visibility for sex work, for some

OnlyFans’ popularity poses a complex problem for sex workers. Non-sex workers (aka civilians) have increasingly turned to the platform over the pandemic, banking off its reputation for adult content to build their own non-sexual followings. Online influences and celebrities from Cardi B to Zelina Vega to Bella Thorne have tried their hands at the site, too, with Thorne going so far as to erroneously claim she “took a hit” for “doing it first.”

Meanwhile, sex workers on OnlyFans have faced surmounting problems parallel to the platform’s rise to fame. Changes to the site’s referral program have harmed sex workers’ income. Long load times and outages became increasingly more common on the site as celebrities caused traffic spikes.

Perhaps most noteworthy of all is the whorephobic backlash against sex workers on and off OnlyFans. Far-right figures like Matt Walsh have argued sex work “is not real work” and called it “self-debasement for profit,” kicking up a frenzy against both sex workers and their clients. Journalists have increasingly covered OnlyFans models in whorephobic and voyeuristic ways, such as the New York Post writer who doxed a New York City paramedic on OnlyFans.

Schwarz says OnlyFans’ popularity “certainly increases sex workers’ risk for hypervisibility” and pointed to the paramedic’s doxing. This, she said, represents how mainstream media is “eager to sensationalize [sex workers’] stories and capitalize on persistent stigma and myths.”

“Since OnlyFans has risen in popularity, I’ve heard people opine on it (usually insultingly) who I bet had never before spared a thought to online sex work. Unfortunately, the term ‘OnlyFans’ has now been adopted into the common whorephobic lexicon,” Schwarz told the Daily Dot. “With that said, I don’t blame that on [OnlyFans]; whorephobia isn’t new, no matter how it changes its face.”

This visibility doesn’t help sex workers creating content outside of the OnlyFans ecosystem, either. Take Sanctuary, which is already an outlier as a queer strip club. Most strip clubs generally aren’t run with queer clients in mind, if not outright cultivating heteronormative communities that make queer visitors feel unwelcome, Shakti told the Daily Dot. At Shakti’s club, BIPOC strippers, queer strippers, and fat strippers are given room to not just dance but thrive in doing so. Holliday’s Sanctuary Noire donates ticket proceeds to a given cause (in December, it’s Enby, the Black-owned sex toy retailer).

Unlike most real-life strip clubs, marginalized sex workers’ needs were always at the center of Sanctuary’s creation. Shakti, for example, carefully created Sanctuary’s business model to assure models are treated fairly: Dancers retain 100% of their tips and fill out anonymous feedback forms so they can openly provide criticism.

On the one hand, this cultivates an ethical business model that makes sure sex workers are treated fairly and have their work celebrated in and out of the club. But Shakti says it’s been “really, really, really difficult” to grow the club, in part because queer people (especially those socialized femme) “just typically aren’t told that strip clubs are a place for them.” This, combined with the club’s focus on supporting and highlighting trans, fat, disabled, Black, and Brown dancers, poses a challenge for drumming up mainstream interest in the club.

Theoretically, OnlyFans could use its standing to help marginalized sex workers like Sanctuary and its dancers, but it won’t. If anything, OnlyFans seems uncomfortable with its adult stars, and its performers are constantly concerned the site will continue to make changes for the worse. And OnlyFans’ popularity doesn’t inherently uplift sex worker-run projects like Sanctuary, which forces Shakti to hustle for publicity for the club.

Shakti criticized the way OnlyFans operates, comparing it to Pornhub and arguing that both companies are “unethical.” This is because OnlyFans isn’t necessarily connected with the sex worker community itself, nor is it invested in protecting sex workers and engaging with their struggles, Shakti said.

In this way, OnlyFans may help sex workers as one income source or even help performers stay afloat during a financially precarious situation in their lives. But OnlyFans’ popularity won’t help all sex workers receive the support they deserve, nor is it built with the community in mind.

“The best and biggest thing that you can do right now, especially if you don’t have the funds to come throw money at a bunch of dancers or book a private session with your favorite provider or what-have-you, is to get the word out,” Shakti said. “Come into a show for a little bit, you don’t have to throw a ton of cash. We love seeing faces, we love meeting new people, we love introducing new people to Sanctuary.”

The age of OnlyFans

OnlyFans poses a difficult dilemma for the sex-working community. The pandemic brought in a slew of new sex workers via OnlyFans, and these new online sex workers are still learning about basic safety, their community’s history, and the larger fight for sex workers’ rights. These newcomers may spread internalized whorephobia or encourage risky practices. This means sex workers with more experience within the sex-working community may simultaneously express concern for newer sex workers’ safety while also finding their political beliefs underdeveloped.

“Obviously there’s going to be harm done from all the influx of newbies that come into any sort of industry, doesn’t matter what you’re doing. But there’s always people that are there longer than you have been,” Blue said. “So, how do we approach that from an aspect that feels restorative? And also learn some new stuff from these younger people too, you know? Maybe they have some things to teach us, and we have some things to teach them too.”

Meanwhile, OnlyFans’ popularity also reveals some of the divides that exist among sex workers. Online performers have their own, unique set of issues that do not necessarily align with other sex workers’ needs and concerns, such as online censorship and platform moderation. In this way, OnlyFans and its effect on sex workers show a series of contrasts. On the one hand, certain sex workers’ issues, such as adult performers’ experiences and concerns, are rendered more visible. But other kinds of sex workers, such as full-service sex workers who are still working offline, are still left undersupported. Or they may experience whorephobia from OnlyFans models who insist they are different (or “better”) than their full-service colleagues.

Then there’s the ever-changing nature of doing sex work online. After Mastercard and Visa pulled out of Pornhub in December, sex workers that rely on the site to pay the bills had their payments delayed. Instagram’s terms of service are increasingly clamping down on sex work, and TikTok is reportedly pushing sex workers off its platform. Just this month, Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) and Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) introduced the Stop Internet Sexual Exploitation Act (SISEA), which introduces punitive content moderation systems that could force social media networks to purge adult content on the internet altogether.

Sex workers face difficult and uncertain times up ahead, and OnlyFans is not a safety net for them. But that does not mean the future looks inherently bleak. Holliday believes sex work will go increasingly underground next year as sex workers recover from online censorship on social media, which could lead to a boom for people in the sex trade.

“Because we’re going more underground, there’s going to be a boom for us. What’s done in the dark will always come to light. So I think it’s going to be rocky for a little bit, but it’s going to boom,” Holliday said. “After that boom, sometimes shit goes back down, or it plateaus. To be honest, I hope that it plateaus, because plateaus means a steady pace.”

Sex workers are resilient in the face of oppression, and Holliday isn’t the only one who’s cautiously optimistic. Schwarz believes there is a chance for a better future in 2021, despite the ongoing pandemic and “the endless bipartisan barrage of attacks on sex workers’ rights.”

“What makes me hopeful is seeing sex worker activists and our allies getting more vocal and making stronger connections through mutual aid, especially my fellow queer women of color,” Schwarz said. “We’re the future we’ve been waiting for.”