I got my start in adult entertainment with a three-month editing and production assistant gig working under Van Darkholme at Kink.com. At the same time, I was interning at the Center for Sex and Culture and working as a literary intern for Madison Young. This was in San Francisco in 2014.

In a wider lens, culturally, it was another year of the senseless killing of Black men and women at the hands of the police. It was the year Eric Garner was choked to death at the Hands of the NYPD, it was the year Michael Brown was shot to death in Ferguson, Missouri.

It was another year of gentrification in the city, as the census shows the Black population, and only the Black population, dropping consistently since 1970. One may speculate this had something to do with Black families being priced out with the increasing rent in San Francisco. There was something in the air, a revolutionary potential being made clear to the public at large. People were standing up, protesting, and speaking out. In the pornography industry, it was no different.

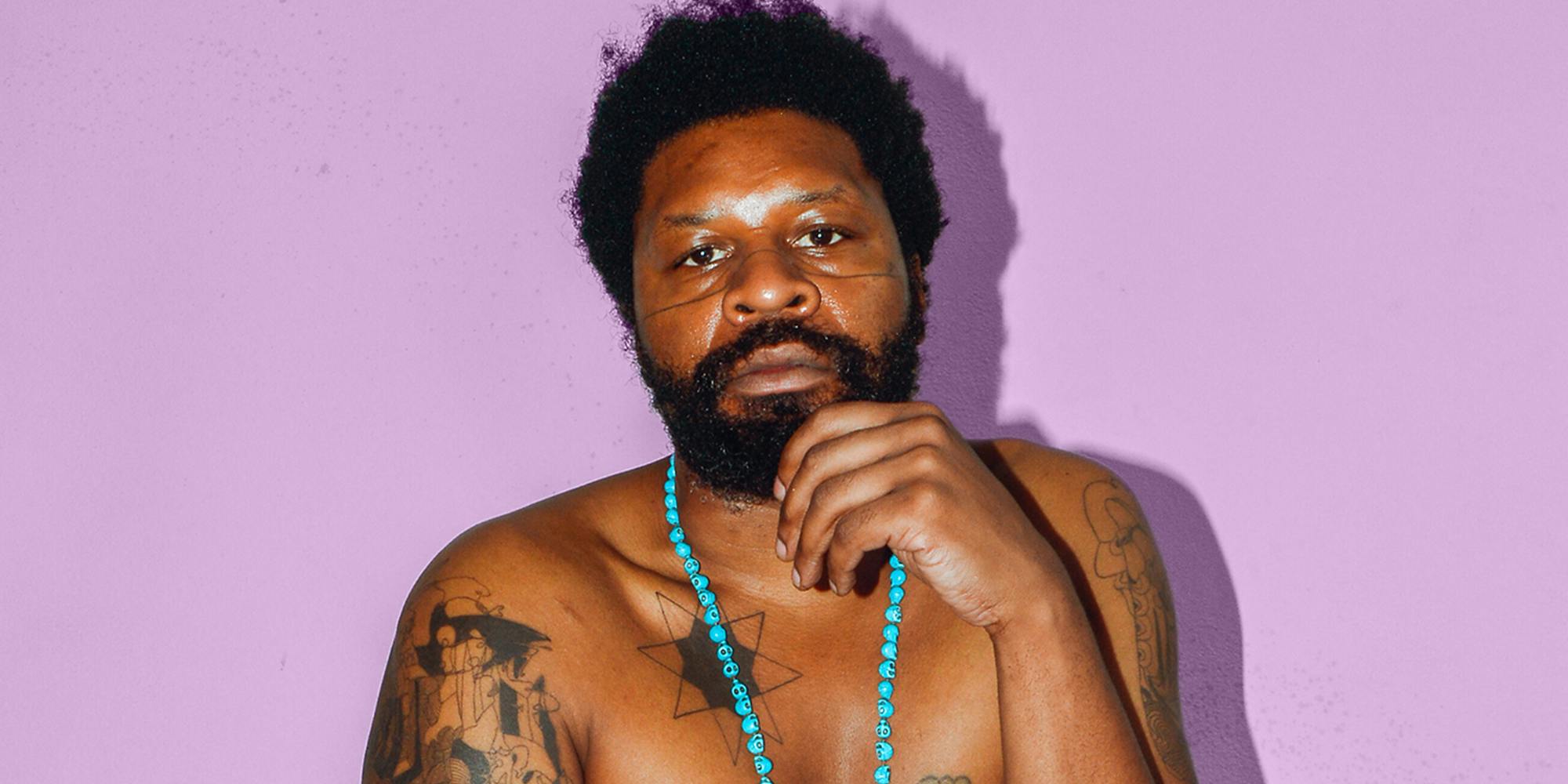

One of my coworkers at the time, Mickey Mod, voiced his concerns about racism in the adult entertainment industry. In a Vice article, he shared a poignant point: “For people of color, there is an unstated suggestion that they are of lower value.” Mod’s sentiments weren’t the beginning of the conversation, but a continuation of the question of how race and sex in American society have shaped a worldview that extended to our industry.

It is the question of how we maintain our identity and self-determine in the face of capitalism’s ever-open mouth. We live in a visual culture and one increasingly marked by our divides. We are exoticized, vilified, underpaid, and partitioned as others in an already sexualized and charged circumstance, our bodies prized for their beauty and power yet divorced from our humanity.

“It’s a business of relationships,” was the advice given to me by John Johnson. The driving force behind my entry into porn was to see something of myself on the screen. Pornographic depictions of Black masculinity are tricky. One of the largest market shares featuring Black performers like myself is Blacked.com.

Blacked presents and perpetuates racist stereotypes through its content and marketing. After all, as performer Demi Sutra tweeted recently, “What if blacked was called Jewished and it featured stereotypical Jewish men dominating white women. Then would you care?? My culture is not a verb. You cannot be “blacked”. How is this not a bigger issue? Is money just really blinding yall? Think about it. Asianed, whited, etc.”

The studio she’s referring to is owned by Greg Lansky with small pools of male talent. The female side of the branding features almost exclusively White women. The Interracial genre is a genre synonymous with the Black and White race play.

This framework is perpetuated because of its profitability and a societal fascination with Black sexuality that is as old as the United States. Blacked has been featured across media platforms GQ, Men’s Health, Forbes, BBC, and others. These publications platform the studio’s “genius” for producing with an aesthetic that many people find desirable without really getting into the political body of why the content is so successful. Long story short, it’s about representation at a base level, a multifaceted word with many implications for a lot of people and one attached to a lot of money in a few hands.

I am Pansexual, I am Black, I am Queer, where do I fit inside of an industry that still makes most of its money off of heteronormative, chauvinistic, and racist caricatures of who I am as a person?

The inflexibility of masculinity presented on camera a skewed vision of the richness of pleasure that we experience as performers in our lives holds as many pitfalls for our health as performers. Audiences have so much access to who we are on and off camera, the call for authenticity being louder than ever, it can be difficult to find ourselves in whole without some serious introspection of who we want to be in the world, work that is often costly and time intensive.

A few months after I stopped working as a production assistant, I was contacted by a producer friend of mine from Kink.com and was booked for my first gangbang for a private investor. Somewhere, there is a DVD of me gangbanging a White woman named Sarah with John Johnson, several other Black performers, and Bill Bailey (RIP).

The independent porn market has long given a place for Black creativity to thrive in place of the studio-driven market. I can remember late-night pay-per-view of Luke’s Peep Show and performers like Jada Fire on VHS being some of the independent pornography I’d seen on a screen. As the internet became widely available and access to a/v equipment became cheaper, the revolution of cam and independent porn has given lots of livelihoods to performers and producers of pornography that would otherwise be marginalized.

King Noire, one half of Royal Fetish Films, presents a vision of what independence looks like. Royal Fetish is a Black-owned BDSM production company that specializes in the kind of content that has traditionally been dominated by white content producers and larger studios.

With his partner Jet Setting Jasmine, Royal Fetish Films is a vocal presence giving testament to the experiences faced being Black in adult entertainment. Noire’s content under Royal Fetish is a cornucopia of bodies engaging in sensual, passionate, and creative sex with a kind of joy that we all aspire to. Similarly, John Johnson has continued to bring high-quality, homegrown images and videos with fresh talent and industry veterans alike.

For me, this is an exciting time. While continuing to perform, I have also produced and directed my first short starring King Noire and Natassia Dreams as part of a publication I launched called DELIGHT Quarterly. At the end of the day, I am an artist and my reasons for creating are an examination of where art, sex, and society converge. I find no greater place to do that than in the frontier of pornography.